Stroke patients with shoulder pain- Physiotherapy Management

Shoulder pain affects from 16% to 72% of patients after a cerebrovascular accident. Hemiplegic shoulder pain causes considerable distress and reduced activity and can markedly hinder rehabilitation. The aetiology of hemiplegic shoulder pain is probably multifactorial. The ideal management of hemiplegic stroke pain is prevention. For prophylaxis to be effective, it must begin immediately after the stroke. Awareness of potential injuries to the shoulder joint reduces the frequency of shoulder pain after stroke. The multidisciplinary team, patients, and carers should be provided with instructions on how to avoid injuries to the affected limb. Foam supports or shoulder strapping may be used to prevent shoulder pain. Overarm slings should be avoided. Treatment of shoulder pain after stroke should start with simple analgesics. If shoulder pain persists, treatment should include high intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation or functional electrical stimulation. Intra-articular steroid injections may be used in resistant cases.

Leandri et al evaluated the effectiveness of high intensity versus low intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) versus placebo for patients with hemiplegic shoulder pain. Low intensity TENS involves electrical stimulation just above the level of the skin sensory threshold. High intensity TENS is sufficient to elicit muscle contraction and an almost painful sensation. The investigators found that patients who received high intensity TENS had significant improvements in passive range of motion for flexion, extension, abduction, and external rotation at the shoulder. The patients who received high intensity TENS also reported very satisfactory pain relief.

Shoulder pain affects from 16% to 72% of patients after a cerebrovascular accident. Hemiplegic shoulder pain causes considerable distress and reduced activity and can markedly hinder rehabilitation. The aetiology of hemiplegic shoulder pain is probably multifactorial. The ideal management of hemiplegic stroke pain is prevention. For prophylaxis to be effective, it must begin immediately after the stroke. Awareness of potential injuries to the shoulder joint reduces the frequency of shoulder pain after stroke. The multidisciplinary team, patients, and carers should be provided with instructions on how to avoid injuries to the affected limb. Foam supports or shoulder strapping may be used to prevent shoulder pain. Overarm slings should be avoided. Treatment of shoulder pain after stroke should start with simple analgesics. If shoulder pain persists, treatment should include high intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation or functional electrical stimulation. Intra-articular steroid injections may be used in resistant cases.

Occurence:

Shoulder pain is a common complication after a cerebrovascular accident. From 16% to 72% of stroke patients develop hemiplegic shoulder pain. It may occur in up to 80% of stroke patients who have little or no voluntary movement of the affected upper limb.

Hemiplegic shoulder pain has been shown to affect stroke outcome in a negative way. It interferes with recovery after a stroke: it can cause considerable distress and reduced activity and can markedly hinder rehabilitation. Royet al demonstrated that the presence of hemiplegic shoulder pain is strongly associated with prolonged hospital stay and poor recovery of arm function in the first 12 weeks after stroke.

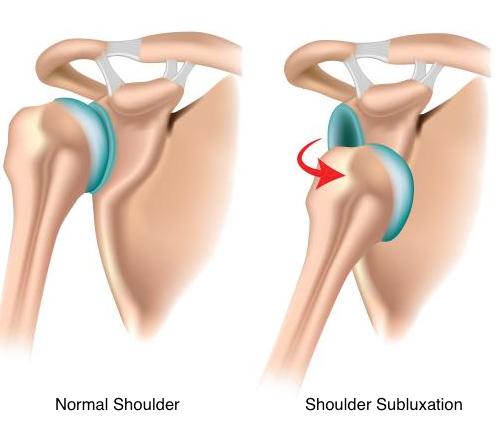

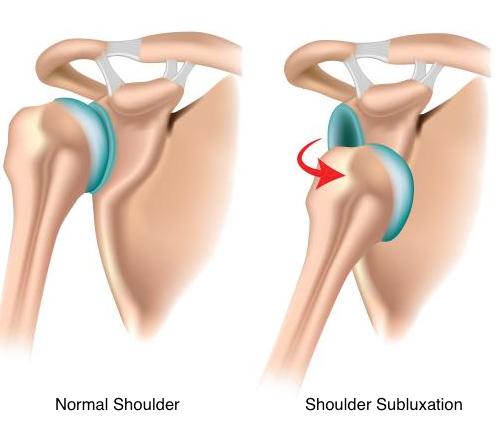

The cause of hemiplegic shoulder pain is the subject of considerable controversy. The following processes have all been postulated as causes of a painful hemiplegic shoulder: glenohumeral subluxation, spasticity of shoulder muscles, impingement, soft tissue trauma, rotator cuff tears, glenohumeral capsulitis, bicipital tendinitis, and shoulder hand syndrome.Traction neuropathy of the brachial plexus may also play a part. Unusual patterns of motor recovery or spasticity or unusually severe focal atrophy may suggest brachial plexus injury. Poor handling of a hemiplegic limb may exacerbate a pre-existing condition such as osteoarthritis. Thus, pre-morbid disease of the shoulder may predispose to hemiplegic shoulder pain. Stroke patients may suffer from pain that is caused by the stroke itself (central post-stroke pain). The role of central post-stroke pain in the aetiology of hemiplegic shoulder pain is uncertain. Abnormal tone (both spasticity and flaccidity) has been suggested as an aetiological factor in hemiplegic shoulder pain. However, clinical observations suggest that shoulder pain does not occur until spasticity develops. Most authorities agree that the aetiology of hemiplegic shoulder pain is probably multifactorial.

Prevention:

The ideal management of hemiplegic stroke pain is to prevent it happening in the first place. Various strategies have been employed in the prophylaxis of hemiplegic shoulder pain. For prophylaxis to be effective, it must be begin immediately after the stroke. Once the patient has pain, resultant anxiety and overprotection will follow.

HANDLING

Poor handling and positioning of the affected upper limb in stroke patients contribute toward shoulder pain.

The mobility of the recovering stroke patient is dependent on the assistance of nurses, therapists, doctors, other ancillary staff, and family members. It is also dependent on his/her own efforts. Handling, positioning, and transferring on a day-to-day basis can exert great stress on the vulnerable shoulder. The problem may be exacerbated by the patient's sensory and perceptual deficits. There has been concern that trauma to the constituent components of the shoulder joint may be caused by poor handling of the patient's affected arm.

Wanklyn et al studied the prevalence of hemiplegic shoulder pain and associated factors in patients with stroke. Sixty three per cent of the patients developed hemiplegic shoulder pain in the first six months after their stroke. Patients who needed help with transfers were more likely to develop hemiplegic shoulder pain. Certainly, patients with markedly decreased voluntary movement after a cerebrovascular accident frequently experience shoulder joint malalignment or subluxation in the early stages of recovery.

Careful positioning and handling of the limb are thought to prevent hemiplegic shoulder pain, but there is a range of opinions about how correct limb positioning is best achieved.

Braus et al investigated the efficacy of an information and education programme in the prevention of hemiplegic shoulder pain. All members of the diagnostic and therapeutic team as well as patients and their family were provided with instructions on how to avoid injuries to the affected limb. The investigators found that awareness of potential injuries to the structures of the shoulder joint reduced the frequency of shoulder pain from 27% to 8%.

Fitzgerald-Finch et al advocated the use of the Australian lift when handling these patients: they felt it to be of value as the weight of the patient is taken on the shoulders of the carer and the patient's shoulder is protected.

STRAPPING

Glenohumeral joint subluxation may be a contributing factor in the development of shoulder pain in this group of patients. Shai et alhypothesised that earlier radiological diagnosis of subluxation might enable more effective prevention than if it is delayed. However, this has not been proved. Despite this, a variety of slings have been designed to try to correct subluxation and pain in stroke patients with hemiplegia. Not all such devices have been successful: supportive devices developed by Buccholtz Moodie et al and Williams et al were not proved to be effective in correcting subluxation of the shoulder.

Physiotherapists have employed various forms of strapping designed for shoulder pain or subluxation after a cerebrovascular accident. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of many of these strapping methods remains largely unproved. Ancliffe undertook a pilot study to determine the effectiveness of a strapping technique to prevent shoulder pain after a stroke. The pilot study demonstrated that strapping the hemiplegic shoulder delayed the onset of shoulder pain. In patients with subluxation and shoulder pain, use of a Varney brace has been reported to be successful: patients become asymptomatic within seven days.

External support can be discontinued when muscle tone around the glenohumeral joint is sufficient to prevent subluxation. An exercise programme should always accompany the use of a sling.

However, a number of authors have reported that slings may hold the limb in a poor position that is likely to cause soft tissue contracture and have an adverse effect on symmetry, balance, and body image.

PHYSIOTHERAPY

Some studies have noted that passive abduction of the hemiplegic arm can result in rotator cuff injury: this in turn causes shoulder pain.

However, therapeutic range of motion exercises done by the patients can involve passive abduction of the arm. Kumar et alanalysed the occurrence of pain in patients receiving three different rehabilitation exercise programs: range of motion by the therapist, use of a skateboard, and use of an overhead pulley. They found that patients who used the overhead pulley had the highest risk of developing shoulder pain and concluded that use of the pulley should be avoided during stroke rehabilitation.

If impingement during range of motion exercises is determined to be the cause of hemiplegic shoulder pain, the amplitude of passive movement should be kept within the pain-free range. Caldwellet al reported that pain subsided in 43% of patients with hemiplegic shoulder pain when the amplitude of passive range of motion was reduced.

Increase in the prevalence of shoulder pain in the first weeks after discharge in patients who did not continue to exercise properly.

Treatment

Radiological investigations should exclude dislocation or fracture of the shoulder before further management is instigated. Various treatments have been suggested as being beneficial in shoulder pain after stroke: these include physiotherapy, localised cooling, infrared, ultrasound, and intra-articular injections of steroids and local anaesthetics. Until recently there has been a shortage of prospective controlled clinical trials.

PHYSIOTHERAPY

Physiotherapy has been used in the treatment of hemiplegic shoulder pain. There are two major approaches to therapy in this field: those that focus on the problem as a localised mechanical one; and those that view the problem as a neurological one. Local treatments used have included heat and cold therapy. Slings and shoulder supports have also been used. Positioning is also considered important by many authors. Other physiotherapy approaches include those of Bobath, Brunnstrom, and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation. Until recently, the evidence for the effectiveness of these methods of physiotherapy has been poor. Partridge examined the effectiveness of two methods of physiotherapy in the treatment of hemiplegic shoulder pain: cryotherapy or the Bobath approach. The cryotherapy approach involved the application of ice to the affected shoulder. The Bobath approach is a neurologically based holistic approach that is frequently used in the UK.

There were no significant differences between the two treatments in terms of severity of pain at rest or on movement or for reported distress. However the proportion of patients who reported no pain after treatment was greater in those who received the Bobath approach.

TRANSCUTANEOUS ELECTRICAL NERVE STIMULATION

Leandri et al evaluated the effectiveness of high intensity versus low intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) versus placebo for patients with hemiplegic shoulder pain. Low intensity TENS involves electrical stimulation just above the level of the skin sensory threshold. High intensity TENS is sufficient to elicit muscle contraction and an almost painful sensation. The investigators found that patients who received high intensity TENS had significant improvements in passive range of motion for flexion, extension, abduction, and external rotation at the shoulder. The patients who received high intensity TENS also reported very satisfactory pain relief.

FUNCTIONAL ELECTRICAL STIMULATION

There are have been a number of studies of the effectiveness of functional electrical stimulation (FES) in shoulder pain after stroke.

Faghri et al studied the effects of a FES treatment programme designed to prevent glenohumeral joint stretching and subsequent subluxation and shoulder pain in stroke patients. They demonstrated a beneficial effect on subluxation and improvement in other parameters such as pain, range of motion, and arm function.

Chantraine et al completed a long term controlled study of the use of FES in hemiplegic stroke patients diagnosed with a subluxed and painful shoulder. They found that a 24 month FES programme was effective in reducing the severity of subluxation and pain and may have facilitated recovery of shoulder function in these patients.

As an extremely mobile joint, the shoulder sacrifices stability for mobility. Basmajian determined through electromyographic studies that the supraspinatus, and to a lesser extent the posterior deltoid muscles, played a key part in maintaining glenohumeral alignment. Chaco and Wolf also demonstrated the importance of the supraspinatus muscle in preventing downward subluxation of the humerus. Two studies have investigated the application of electrical stimulation to the supraspinatus and posterior deltoid muscles: Baker and Parker demonstrated the beneficial effects of FES in stroke patients with a chronic shoulder dislocation. However, patients deteriorated after withdrawal from treatment though not back to pre-treatment levels. Linn et al carried out a prospective randomised study to determine the efficacy of FES in the prevention of shoulder subluxation in stroke patients. They found that FES does prevent shoulder subluxation, but this effect was not maintained after the withdrawal of treatment.

Best information tq

ReplyDelete